By Tom Hearn, Aftercare Team – Wakai Waian Healing

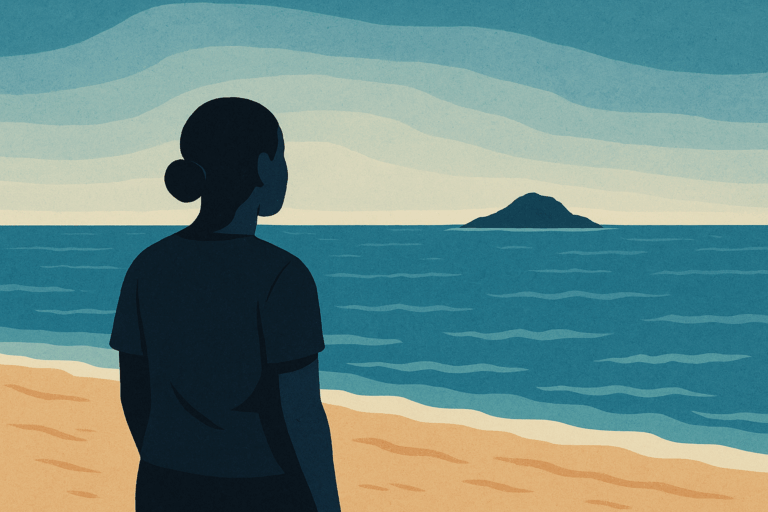

Across the Aftercare consultations, one word keeps returning: isolation. Not only the kind that comes from living far from cities or services, but a quieter and deeper kind. The kind that lives in the heart, in the language, and in the spaces between systems and culture. When you live on an island surrounded by sea, isolation is part of the landscape. But in Zenadth Kes, isolation takes many forms. It can be geographic, emotional, cultural, spiritual, or systemic.

Life on an Island

Imagine a life where your family has lived on the same island for thousands, of years. Your ancestors’ stories are woven through the reef, the tides, and the stars. Everyone knows one another. The rhythms of the sea shape your week.

Yet this closeness can bring its own kind of weight. You might know everyone on your island, but who knows you outside of this? Who truly understands your island, your people, your kustom, your language?

In larger health systems, education, and government, few people see what life feels like in a place so small, so far away, and so deeply connected. The experience of isolation in Zenadth Kes is not only about distance. It is the sense of being surrounded by people, yet still unseen by the world beyond the reef.

For some, this isolation feels like invisibility. For others, it is a quiet ache – a longing for the wider world to understand the complexity and beauty of island life. When mainland systems fail to recognise local language, kinship, or decision-making structures, people feel not only physically cut off but psychologically and culturally unseen.

This form of isolation can intensify distress. It is not loneliness in the usual sense, but a kind of cultural aloneness – being known within your island but misunderstood beyond it. Over time, that gap between inner and outer worlds becomes part of the island people’s mental load.

As one participant in the consultations said, “Our island is small, but our world is big inside it. The problem is no one outside can understand it.”

More Than Geography

Research into remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities has long shown that isolation is not only about geography. It is social, cultural, and structural. When access to services, education, and opportunity is limited, and when decisions are made far away, isolation becomes a system rather than a circumstance.

Psychologists sometimes call this cultural isolation, the feeling of being cut off not only from other people, but from a sense of voice and power. It can lead to what researchers describe as disempowered belonging, where people feel deeply connected to their place but excluded from the structures that shape their lives.

Emotional and Psychological Isolation

Through the consultations, people speak about loneliness that goes beyond being alone. It is the loneliness that comes when the world no longer speaks your language, both literally and metaphorically.

Younger people describe feeling between worlds, pulled by social media and mainland expectations on one side, and by the responsibilities of culture, family, and island identity on the other. Elders talk about grief, for language, for custom, for the slowing of once strong traditions.

This form of isolation often hides behind humour and resilience, but it sits close to the surface. As one participant shared, “Sometimes you feel like you are the last one holding something precious, and you are not sure who to hand it to next.”

Linguistic and Spiritual Isolation

Language holds culture, identity, and relationship. When someone cannot express their emotions in their first language, or when that language has no space in schools, clinics, or courts, a layer of silence builds between people and systems.

The same is true for spirituality. Faith in the Torres Strait takes many forms, but for many, wellbeing is bound to sea, season, and ceremony. When those rhythms are broken by relocation, by cost of living, or by policy decisions, people can feel spiritually adrift.

As one Elder said, “You cannot separate the spirit from the tide. When the tide is out too long, something inside you dries up.”

Isolation Within Isolation

Every island has its own way of being its own dialect, dances, and laws of respect. That is the strength of the Torres Strait. But it also means that isolation can happen even across short distances. Islanders can feel distant from each other when those differences are not respected or understood.

Each community’s way of healing is unique. The Aftercare consultations remind us that there is no single story of isolation, just as there is no single path to reconnection.

Reconnection as Healing

Through the Aftercare consultations, we are hearing about the many layers of isolation that people live with every day. But our work at Wakai Waian Healing has been responding to this long before these consultations began. For more than a decade, our therapeutic work across the Torres Strait and mainland communities has been quietly healing this same sense of isolation – restoring connection to self, family, culture, and spirit.

Every counselling session, group program, outreach visit, and moment of listening is part of that healing. When we sit with people, when we honour their stories and strengths, we are helping rebuild the bridges between worlds that isolation has pulled apart.

So let’s keep going. The work we do each day – in homes, clinics, schools, and community spaces – is helping people feel seen, heard, and connected again. This unity and connection is the heart of what Wakai Waian Healing stands for.