Sitting on the Sand at St John’s

Wakai Waian Healing travelled to Masig Island for Aftercare consultations. These consultations, commissioned by the North Queensland Primary Health Network, are a regional listening exercise. The aim is simple and serious. To sit with the people of Zenadh Kes and ask them what support they need after a suicide attempt or a mental health crisis, and how these services should look on their islands, in their homes, shaped around their language, culture and old family systems.

It is no accident that NQPHN chose Wakai Waian Healing to lead the process. Ed Mosby, senior psychologist and the organisation’s founder and CEO, is a Torres Strait Islander man. His family is the Mosby family. His bloodline is woven into Masig. His leadership is grounded in culture, language and old responsibilities. Wakai Waian Healing is not an outside service visiting the islands. It is an Islander founded and led organisation. When the PHN asked for true cultural consultation, Ed was the right person and Wakai Waian Healing was the right Organisation to do this work properly. The work required someone who knew the people, the language, the rhythms of Island life, and who could sit with Elders and be guided, not guide them.

When we arrive at St John the Evangelist Anglican Church, the soft white sand is warm under our feet. The church sits only metres from the beach. Down the road, headstones shaped like coral sculptures rise from the earth. The graves are decorated with flowers, shells and photographs that honour generations. These are not symbols of death but reminders of connection. Masig looks after the living and the departed with the same grace. Good pasin is part of every stone.

Ed pauses and looks around. This is his place. This is where his father, Monty Mosby, who was Uncle Ned’s older brother, ran the island shop. Children remember running in and out, trading raked leaves for lollies. Many adults still remember Monty’s generosity, his calm presence, and the sense that the shop was a place where everyone belonged. People call out to Ed by name. They greet him as if he never left. He comes back regularly to visit family. His place in the community is known. His responsibilities are understood.

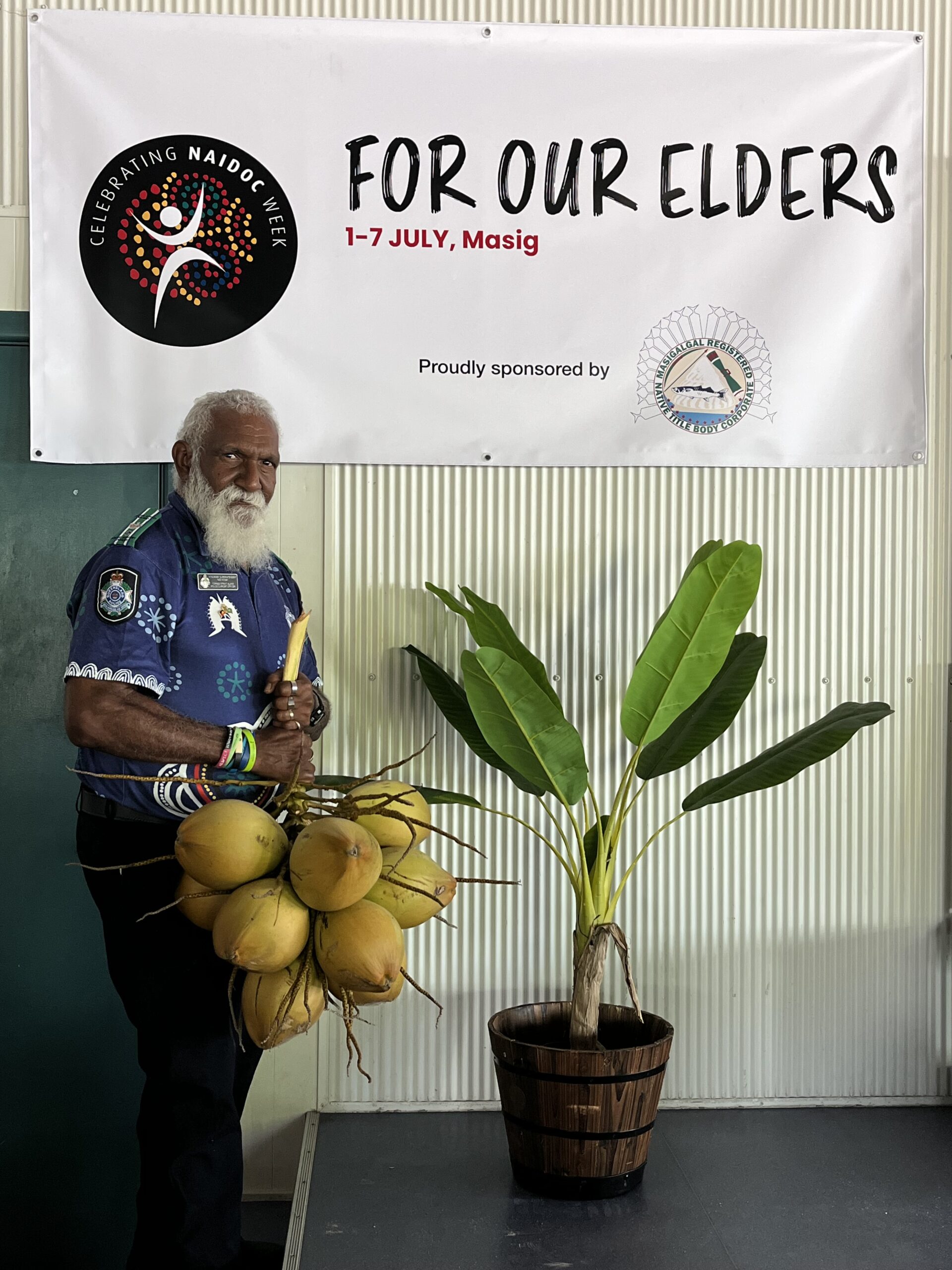

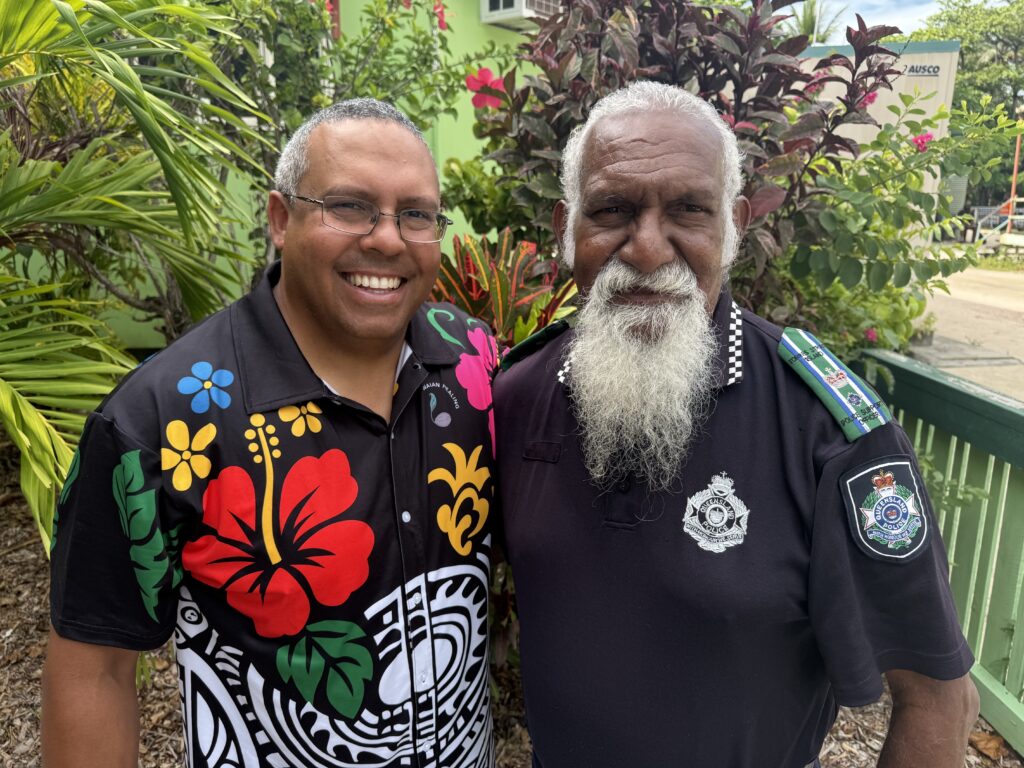

We see an Elder sitting on the sand. This is Ed’s Awa in cultural terms. His Father in the old way. The man who played a role in shaping Ed’s understanding of Masig, culture, faith, and the island’s collective memory.

This is Uncle Ned Mosby.

When Ed steps toward him, the old man’s face breaks into a wide smile. The two embrace with the tenderness of family, of father and son, of mentor and student. There is deep affection and something even deeper, something that feels like legacy.

I sit down just behind them. I am only here to observe. A fly on the wall. My job is to record, but the real work is happening between these two men.

Uncle Ned speaks first.

“Everything here has a story,” he says. “The graves, the church, the sand. Nothing is forgotten here. Family is everything. Good pasin. Praise the Lord.”

The light falls across the old coral walls of the church built in the late 1890’s. It is easy to imagine the early days when families built this church from reef rock, hauling stone by hand and burning coral to make lime. Faith and culture worked side by side in the heat. This island remembers the arrival of the London Missionary Society teachers who came in sailing ships during the Coming of the Light. Islanders stood beside the LMS pastors, cutting timber, preparing lime, lifting beams into place, and shaping a house of worship from the materials the sea and land provided. The church was born from cooperation between old beliefs and the new faith, and it has carried both ever since. This place has always been a house of healing.

The Policeman and the Army Major

Uncle Ned lowers himself into the sand, laughing about his long white beard that hides the fact he has few teeth left. “Dentists don’t visit much,” he laughs. “So the beard does the job. Praise the Lord.”

Beside him sits Ed, tall, quiet, thoughtful. The two share the same humour. Both know how laughter can soften heavy stories.

Uncle Ned has spent a lifetime serving his people. Police officer. Priest. Cultural protector. He has seen grief, violence, overcrowding, loss, the silent pain that sits inside homes. He carries decades of other people’s suffering, yet he still laughs first. His joy is a shield.

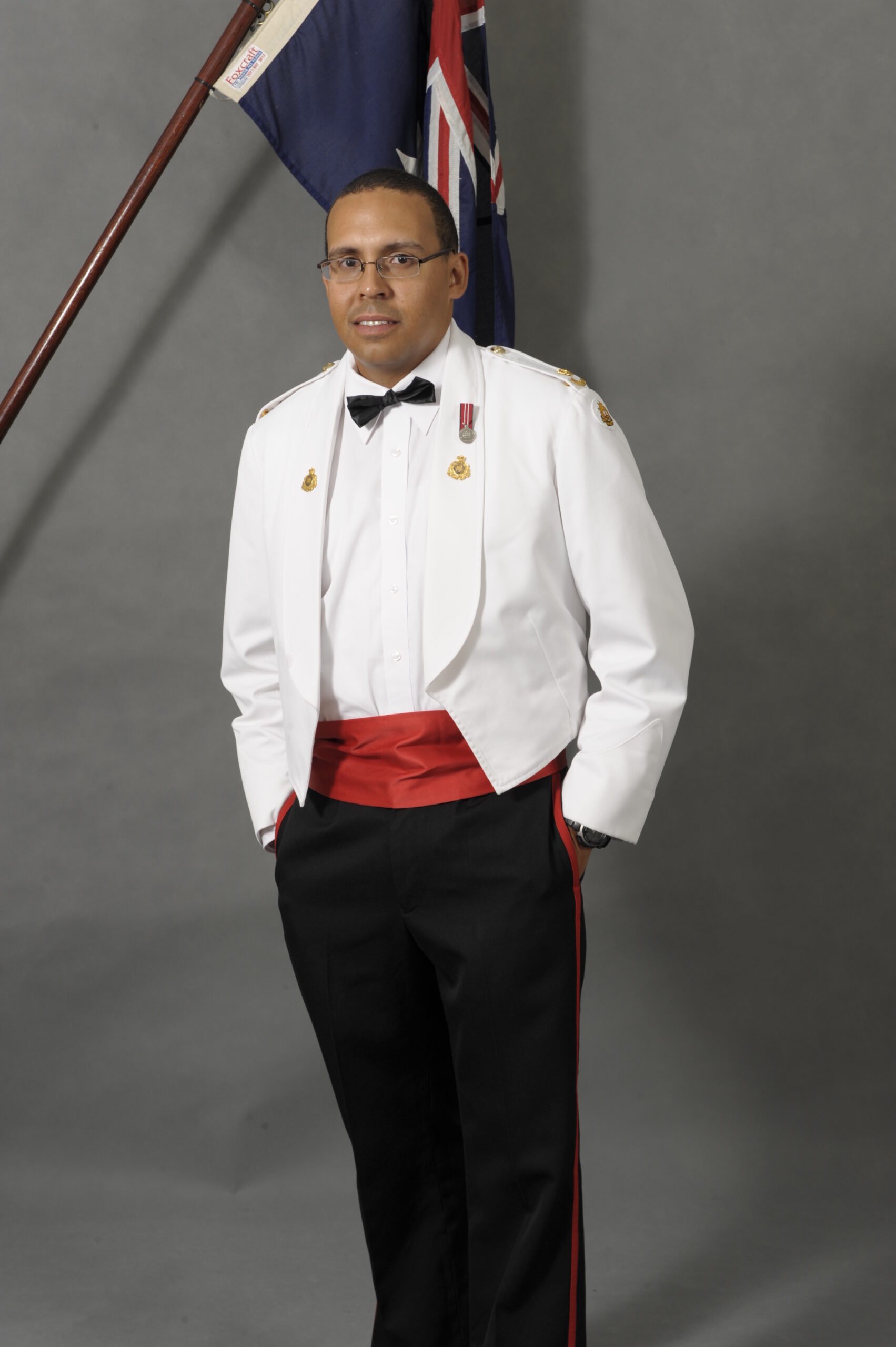

Ed listens with respect. He also carries years of service. Once an Army Major. Now a senior psychologist. Now the founder of an Indigenous mental health organisation working across Queensland and Zenadh Kes.

Two men. Two paths. Both in service. Both leaders in their field. Both Mosbys.

And both love each other in that quiet, unspoken Island way.

Straightening Yarn

Uncle Ned smiles and explains something I have heard many times on this trip but never with this clarity.

He talks about the old Kala Lagaw Ya term ‘Wakai Waian’. It does not mean psychology. There is no such word. It means straightening yarn.

“When an Elder tells a young one, sit down, I am going to Wakai Waian you, that means the Elder is going to encourage you, guide you, straighten your path.”

This is done during initiation, during adolescence, during moments of confusion or shame. It is the cultural heart of mental health support. Encouraging someone to return to their rightful place in the family system.

“Wakai Waian Healing,” Uncle Ned says, “is the right name. Your elders gave you that name because this is what you do. You straighten yarn. You encourage people back into their healthy role.”

He reaches over and squeezes Ed’s arm.

“You are doing what our old people did. Praise the Lord.”

Ed smiles quietly. It is not pride. It is something more like recognition. Something like coming home.

Three Arcs in the Sand

The afternoon settles into a kind of stillness, the kind that comes when something important is about to be shared. Uncle Ned shifts his weight, leans forward and places his hand on the soft sand. With slow, deliberate movements he draws three arcs. They curve like waves folding into one another, simple shapes that seem to hold the whole history of the island. He works with the ease of someone who does not rush knowledge, someone who knows exactly when a teaching should be revealed.

He taps the first arc. “Week one,” he says quietly, “a male counsellor sits with the men. Quiet talk. Men need that.” His voice is gentle but certain, as if describing something the island has always known.

His finger moves to the second arc. “Week two is for the women. A place where they can talk to each other proper. Women hold the family steady. They carry a lot. They need space too.”

He touches the third arc and looks at both of us. A smile softens his face. “And week three, both counsellors come back. Not for heavy talk. For kai kai. Laughter. Games. Music. Good pasin. Bring everyone together again.”

He taps all three arcs at once. “This,” he says, “is how you teach mental health. Make it feel like us. Make it feel like family life.”

Ed watches him with the focus of a son listening to a father. He leans in a little, hands resting on his knees. “Awa,” he says softly, “this has to be done. And it has to be done right.”

Uncle Ned nods as if he expected that. “You can do it,” he replies. “Because you understand the rhythm here. You grew up in it.”

A small silence follows, gentle and warm. The breeze moves across the sand. The three arcs sit between them like a map drawn by the sea itself.

Ed looks down at the shapes again. “It’s simple,” he says, almost to himself.

“Simple is powerful,” Awa Ned answers. “People forget that.”

There is something tender in the way the two men watch each other. A father and son in the cultural sense. A mentor and his student. A leader passing the torch to the next leader. Ed receives the teaching not as a CEO, not as a psychologist, but as a Masigalgal man being reminded of his responsibilities.

Three arcs in the sand. A whole system of care hidden in three strokes of a finger.

The moment feels like revelation, but a quiet one, the way Elders always reveal truth. A teaching offered without ceremony, because the sand itself is ceremony enough. And in this brief exchange, the purpose of Ed’s return to Masig becomes unmistakable. This is why he came. This is what he was meant to hear. This is the centrepiece of the work. Deliver community based mental health education. Ease into delivering psychological services. Build trust first. Practice Good Pasin.

Why Aftercare Matters

Across Zenadh Kes, many people do not understand psychology as a service. There has never been strong mental health promotion on the outer islands. Pastors and priests have always been the first point of care. For some, mental illness is seen as spiritual suffering. Sometimes even a devil.

This is not ignorance. This is history. This is the story of services that never came, or came once, or came too late.

Multiple people have told us that they want more storytelling, more education, more community nights, more culturally grounded mental health support. They want priests and pastors involved. They want messages delivered through local voices. They want counsellors. They want confidentiality. But first they want to understand how it works. And to build trust. You can’t tell your problems to someone if they are going to gossip. After all, every family here is connected, all talk and it’s a small place. Trust is vital. Ed sighs with relief. This is exactly what Wakai Waian Healing is here to learn.

Inside the Old Church

We follow Uncle Ned inside the church. The air smells of timber, salt, old hymns, and more than a hundred years of baptisms, weddings and funerals. The breeze moves gently through the rafters.

Ed takes a seat beside his awa. I sit quietly behind them. This is a moment I know I will never forget. The affection between these two men is visible. Their bond is gentle, dignified, and full of memory. A father and son without needing to be biological. A mentor and a student who has become a leader in his own right. A prodigal son who returns again and again, not lost, but seeking guidance.

Uncle Ned closes his eyes.

“This place holds us,” he whispers. “Even when we forget how to hold each other.”

Ed bows his head. He knows this is true. He knows this is why he came home.

Healing has always lived here. In the rhythm of the island. In the four principles : Respect, Recognise, Do not Abuse and Good Pasin. In family. In the way the departed are cared for with the same love as the living. In the way laughter and grief walk side by side.

The old man lifts his head again.

“It is time,” he murmurs. “Praise the Lord. It is time.”

Beside him, Ed nods.

And somehow, in the cool of St John’s, it feels like the truth.