Why Indigenous-led consultation and cultural governance must come before service delivery

Across Zenadth Kes, communities have been consistent in what they ask for. Aftercare does not begin when a service arrives. It begins earlier, through relationships, trust, and the way people are listened to.

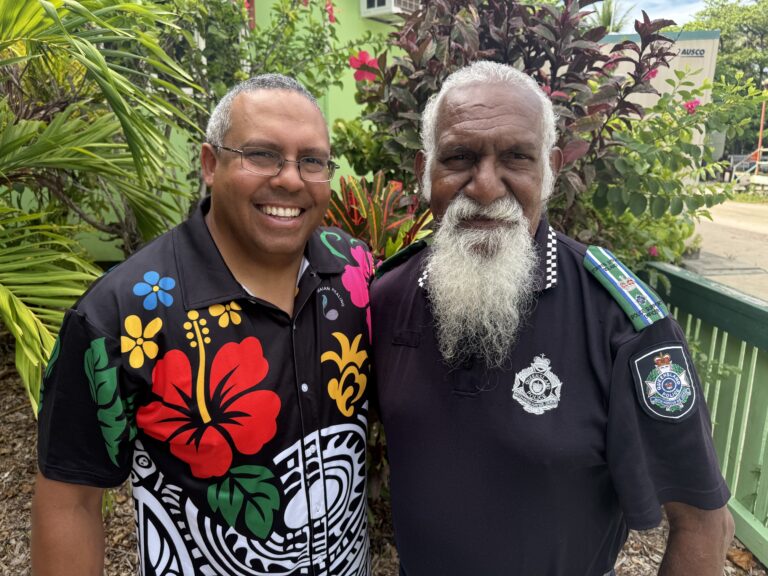

When Wakai Waian Healing was invited to support conversations about aftercare across the Torres Strait, the organisation made a deliberate choice to begin with Indigenous-led engagement. Before any service model was discussed, before delivery decisions were considered, authority was placed with community and the work began by listening.

Elders, families, young people, faith leaders, and local workers were engaged in conversations about distress, loss, and healing in ways that respected local protocols and community rhythms. What emerged was not simply feedback on services, but a clear articulation of how wellbeing is understood and maintained in Island communities, and why consultation must come before any effective response.

For many, the language of aftercare does not easily translate into local understandings of wellbeing. Communities spoke instead about guidance, prevention, and staying connected over time. Elders described Wakai Waian, the practice of straightening someone’s path through conversation, presence, and care. This understanding shaped not only the consultation process, but how authority was held, decisions were made, and responsibility was shared.

Indigenous leadership and cultural governance as the foundation

From the outset, Wakai Waian Healing embedded cultural governance at the centre of the work. Oversight was provided by a Steering Committee of respected Elders and faith leaders from Zenadth Kes. Their role was authoritative, not advisory. They guided the cultural framing, ethics, and integrity of the engagement and validated direction before any movement toward service design.

This governance structure made clear that authority sat with community. It ensured the work was not extractive, that cultural protocols were upheld, and that what was documented reflected lived realities rather than external assumptions.

Alongside this, a Working Group supported coordination, continuity, and accountability. Its role was to carry community guidance forward faithfully, ensuring that consultation flowed into co-design and readiness for delivery without diluting cultural meaning or overriding community authority.

Community Connectors were central to this model. As trusted local leaders, they facilitated introductions, advised on appropriate timing and settings, and ensured engagement occurred in culturally safe spaces. Their presence enabled trust, protected privacy, and ensured conversations were relational rather than transactional.

Together, these elements formed a governance model where Indigenous leadership was primary, engagement was grounded in relationship, and service systems were required to follow rather than lead.

Trust is built through presence, not process

As engagement progressed, communities were clear that effective aftercare depends on trust built over time. Short visits, rotating personnel, and one-off interventions were widely experienced as ineffective and, at times, damaging.

Families described existing systems of care that operate through kinship, culture, and faith. External support that fails to recognise these systems risks disrupting them. What communities asked for was not more activity, but continuity, predictable presence, and known faces.

This has significant implications for aftercare design. Trust is not established through policy or process alone. It is built

through return, consistency, and accountability over time.

Aftercare is collective because wellbeing is collective

Across Zenadth Kes, distress was consistently described as collective rather than individual. When one person is struggling, the impact is felt across households, kinship networks, churches, and the wider community.

This challenges individualised service models that focus primarily on one person at a time. Clinic-based responses alone do not align with community realities and can leave families carrying responsibility without adequate support.

Communities emphasised the importance of staged healing that recognises different roles and pressures within families. Separate spaces for men, women, and young people were described as essential foundations before families come together for collective healing. This approach reflects cultural knowledge and underscores why consultation is necessary to design responses that fit community life.

Safety, privacy, and cultural trust

In small and closely connected communities, privacy is critical. Fear of gossip and judgement can prevent people from seeking help early. These realities reinforce the need for culturally safe, discreet, and relational engagement.

Confidentiality, communities explained, must be demonstrated through consistent behaviour over time. This requires stable relationships, trusted local involvement, and governance structures that prioritise cultural safety rather than speed.

Why this model matters beyond the Torres Strait

The effectiveness of the Torres Strait work lies not only in place, but in process. Across Western Queensland, including communities such as Cunnamulla and surrounding towns, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups have articulated similar expectations. Services must be shaped with communities, not delivered to them.

The principles are consistent across contexts. Indigenous leadership. Cultural governance. Relationship-based engagement. Trust built over time. Consultation is not a delay to service delivery. It is the work.

Walking alongside as a practice standard

Wakai Waian Healing’s approach in Zenadth Kes demonstrates what becomes possible when Indigenous-led engagement and cultural governance are treated as essential, not optional.

Rather than rushing into delivery, the focus has been on listening first, co-designing next, and committing to continuity. This approach strengthens effectiveness by aligning services with how communities understand care, responsibility, and healing.

The message from Zenadth Kes is clear. Aftercare works best when services walk alongside communities, guided by Indigenous authority, grounded in relationship, and accountable to trust. Community-led consultation is not a preliminary step. It is the foundation. And when that foundation is strong, aftercare stops being something delivered and becomes something held, trusted, and sustained over time.

Story by Tom Hearn – Mental Health Reporter